AMR Penetration Increasing

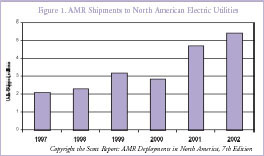

The North American electric utility industry is quickly moving to a point where the debate over whether to deploy AMR will be a thing of the past. As of the end of 2002, there were approximately 25.6 million electric meter AMR units installed. More than one-third of the approximately 3,200 electric utilities (including combination utilities that provide electric service), representing more than three-quarters of all of the approximately 135 million electric meters in North America, have already implemented AMR on some or all of their meters. The rate of deployment continues to grow; shipments in 2002 rose 15% over 2001 (Figure 1).

Compelling Reasons for AMR

Response to the promises of advanced meter reading technology has varied widely. Some utilities have saturated their service territories, while others have opted to concentrate on large C&I customers or “surgical” or “strategic” deployments (e.g., all new construction). A significant portion of utilities has implemented multiple AMR systems to meet the needs of different customer segments. Some utilities have only conducted trials (sometimes several trials).

While many utilities have forged ahead with AMR, others have repeatedly evaluated the technology, but their justification keeps falling short. There are certainly legitimate hurdles: it’s expensive, standards are lacking, and there has been some instability among vendors, raising fears about obsolescence. Deregulation and disaggregation of metering and billing functions, and the potential stranding of metering system investments, are common fears. Utilities are also concerned about unmet expectations, particularly among newer and more sophisticated technologies. Some utilities are concerned about finding a solution that works for all their customers.

Yet there are compelling reasons for considering AMR. As utilities focus more on the bottom line and reduce staff, AMR can help fill the void. Moreover, it enables the radical process improvements that can leverage staff productivity, enhance customer service, and make the utility more competitive. In the current era of volatile raw fuel and purchased energy prices, AMR is becoming an increasingly important tool in shaping load and reducing uncertainty. Pricing signals to customers and more precise modeling and demand forecasting based on AMR capabilities can help the utility better utilize its existing infrastructure. Utilities that need to focus on customer retention can take advantage of enhanced customer services opportunities that AMR supports.

Some Perspective on the Business Case

Over the last several years, AMR technology has grown more capable and cost effective, with larger installed bases. Utilities with more pressing needs, more critical strategic decisions and more straightforward business cases, as well as “early adopters,” have implemented AMR. Meanwhile, as the industry better understands the value of the technology, AMR business cases have become more sophisticated — more benefits are being recognized and validated. For the utilities that have yet to fully explore AMR, and for those that haven’t so far seen an economic “break-through,” this sophistication means that the process of building the business case is more problematic. In fact, building a comprehensive AMR business case itself becomes a project, with many new challenges, among them:

The right answer is the one that is supportable by consensus, achieves the major business objectives, aligns with the utility’s strategies, and generates a return on investment commensurate with the utility’s capital requirements and financial hurdles.

Ultimately, the business case is more than a financial analysis or a report. It is a process involving give and take between the project champions and all stakeholders. The AMR project champion may be able to assert that the system will improve distribution system reliability, for example, but how many line crews will the distribution system maintenance managers agree that they can live without as a result of AMR?

The success of the business case also depends upon the project champion, the study team and the executive sponsor. The project champion should possess vision, enthusiasm, political savvy and familiarity with the organization. The executive sponsor ensures that the project manager and his/her team have access to needed resources and information, and that indirect beneficiaries of the system will commit savings (such as reduced field crews) to the business case. The study team should consist of representatives of various departments or functions that would be impacted by the project. Diversity and a cross-section of reporting levels are helpful. Finding good team members can be tricky, since the most talented people are often the least available.

Systematizing Benefits Analysis

Successful business cases for AMR have common characteristics usually associated with the strategy and process of developing justification and support. Given the challenges, the project’s champions need to (1) adopt a systematic approach to looking at benefits and costs, and (2) build a “campaign” within the organization. While this process is not mechanical, it should be systematic.

A logical starting place for most utilities is to identify the range of available AMR system characteristics and features, and then categorize the benefits created by those features for the utility. Different AMR systems have a wide range of capabilities, from simple gathering of meter readings on a monthly basis (mobile radio), to short-interval monitoring of power quality and outages.

While some benefits of AMR are straightforward, the realization of others will require the involvement of several systems and departments. The following categorization of benefits is useful in developing the campaign to quantify them and win their acceptance.

Simple versus complex. Simple benefits involve only one area, function or department. An obvious example is reducing the number of meter readers needed for on-cycle reading. Complex benefits depend on multiple systems or departments. The identification of abnormally high or low consumption, for example, depends on integrating the meter reading data with consumption histories in the customer information system.

Direct versus Indirect. Some benefits are directly related to the capabilities of the system. For example, the ability to create customer load profiles is directly tied to the system’s ability to obtain numerous reads per day from the meter. Indirect or secondary benefits rely on some process or chain of events. The utility’s call center, for example, may experience a reduction in call volume as a result of eliminating estimated reads. Distribution system operations staff might use missing reads from the AMR system to identify areas of power outage, or detailed circuit related consumption data to balance loads on capacitors and transformers.

Operational versus strategic. Operational benefits pertain more to reductions in operating and maintenance costs or improvements in system reliability. Strategic benefits deal with competitive positioning or long range corporate objectives such as asset optimization or customer retention.

Tangible versus intangible. Tangible benefits can be put in monetary terms; for example, a reduction in staff salaries and overhead. Intangible benefits can’t easily be put in monetary terms, although sometimes they can be quantified. Intangible benefits might include improved air quality and traffic congestion from having fewer vehicles on the roads, improved customer satisfaction, or enhanced corporate image. The utility must not undermine its business case by eliminating obvious benefits because they are difficult to quantify.

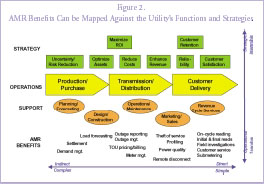

Any such categorization will create some gray areas, and it’s important to put these in context. Figure 2 maps key functions and strategies in a utility. Often, the more direct benefits are larger, but this is not always the case. For some utilities, the indirect or strategic benefits have clinched the business case. What’s important is that the farther away the team reaches from the lower right hand corner to find benefits, the more complex, indirect, strategic and intangible they will be, the more people are involved in quantifying them, and the more people there are to convince.

Steps in the Business Case Campaign

With few exceptions, utilities that have created successful AMR business cases have gone through a process of building support and consensus. The following methodology, extrapolated from the experiences of several projects managers, will help ensure the maximum in expected benefits and a firm handle on the appropriate technologies.

The systematic approach involves the follow steps:

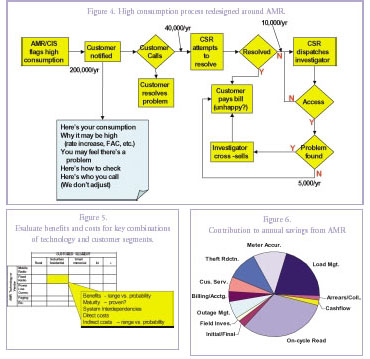

As this process unfolds, more savings will be “contributed to the pot.” Figure 6 is a composite of the contribution in several different areas for some representative electric utilities. The composite total is about $30/customer/year.

Conclusion

Building the business case is similar to waging a political campaign. It requires leadership, creativity, salesmanship, patience and compromise to overcome the challenges and resistance. A systematic approach to classifying benefits, and a process of stakeholder involvement to secure the savings commitments associated with them, will increase chances for success.

Editor’s Note:

Don Schlenger is a Managing Partner with Cognyst Consulting, LLC, and can be reached at dschlenger@cognyst.com. Ed Finamore, an Associate Consultant with Cognyst Consulting, also contributed to this article; he can be reached at EdFinamore@aol.com.

The North American electric utility industry is quickly moving to a point where the debate over whether to deploy AMR will be a thing of the past. As of the end of 2002, there were approximately 25.6 million electric meter AMR units installed. More than one-third of the approximately 3,200 electric utilities (including combination utilities that provide electric service), representing more than three-quarters of all of the approximately 135 million electric meters in North America, have already implemented AMR on some or all of their meters. The rate of deployment continues to grow; shipments in 2002 rose 15% over 2001 (Figure 1).

Compelling Reasons for AMR

Response to the promises of advanced meter reading technology has varied widely. Some utilities have saturated their service territories, while others have opted to concentrate on large C&I customers or “surgical” or “strategic” deployments (e.g., all new construction). A significant portion of utilities has implemented multiple AMR systems to meet the needs of different customer segments. Some utilities have only conducted trials (sometimes several trials).

While many utilities have forged ahead with AMR, others have repeatedly evaluated the technology, but their justification keeps falling short. There are certainly legitimate hurdles: it’s expensive, standards are lacking, and there has been some instability among vendors, raising fears about obsolescence. Deregulation and disaggregation of metering and billing functions, and the potential stranding of metering system investments, are common fears. Utilities are also concerned about unmet expectations, particularly among newer and more sophisticated technologies. Some utilities are concerned about finding a solution that works for all their customers.

Yet there are compelling reasons for considering AMR. As utilities focus more on the bottom line and reduce staff, AMR can help fill the void. Moreover, it enables the radical process improvements that can leverage staff productivity, enhance customer service, and make the utility more competitive. In the current era of volatile raw fuel and purchased energy prices, AMR is becoming an increasingly important tool in shaping load and reducing uncertainty. Pricing signals to customers and more precise modeling and demand forecasting based on AMR capabilities can help the utility better utilize its existing infrastructure. Utilities that need to focus on customer retention can take advantage of enhanced customer services opportunities that AMR supports.

Some Perspective on the Business Case

Over the last several years, AMR technology has grown more capable and cost effective, with larger installed bases. Utilities with more pressing needs, more critical strategic decisions and more straightforward business cases, as well as “early adopters,” have implemented AMR. Meanwhile, as the industry better understands the value of the technology, AMR business cases have become more sophisticated — more benefits are being recognized and validated. For the utilities that have yet to fully explore AMR, and for those that haven’t so far seen an economic “break-through,” this sophistication means that the process of building the business case is more problematic. In fact, building a comprehensive AMR business case itself becomes a project, with many new challenges, among them:

- If the business case is insufficiently detailed and comprehensive, it will suffer credibility and not achieve “critical mass.” At the same time, however, the investigation can fall into “analysis paralysis” trying to pin down enough details and uncertainties.

- Both the “target” and the “shooter” are moving: the utility’s operating and regulatory environment, the technologies and the AMR marketplace are constantly changing, even over the course of the business case study.

- The more complex the benefits, the harder they are to quantify and the more resources required to evaluate them and convince others of their validity.

- The number of dimensions (customer segments, technologies, benefit areas, etc.) and variables in the business case can easily generate an extraordinary number of permutations. Considering them all can be overwhelming.

- Depending on their starting orientation, the same methodology can easily lead the team to a different conclusion. If the investigation is initiated at an operational level in meter reading, for example, the business case is likely to look different than if it stated in customer service, distribution operations, or at the executive level.

- There is no way to arrive at the “correct” or “perfect” answer. Every time the study team looks at a situation, they will see it a different way. This could lead to a situation where the business case is never quite completed.

The right answer is the one that is supportable by consensus, achieves the major business objectives, aligns with the utility’s strategies, and generates a return on investment commensurate with the utility’s capital requirements and financial hurdles.

Ultimately, the business case is more than a financial analysis or a report. It is a process involving give and take between the project champions and all stakeholders. The AMR project champion may be able to assert that the system will improve distribution system reliability, for example, but how many line crews will the distribution system maintenance managers agree that they can live without as a result of AMR?

The success of the business case also depends upon the project champion, the study team and the executive sponsor. The project champion should possess vision, enthusiasm, political savvy and familiarity with the organization. The executive sponsor ensures that the project manager and his/her team have access to needed resources and information, and that indirect beneficiaries of the system will commit savings (such as reduced field crews) to the business case. The study team should consist of representatives of various departments or functions that would be impacted by the project. Diversity and a cross-section of reporting levels are helpful. Finding good team members can be tricky, since the most talented people are often the least available.

Systematizing Benefits Analysis

Successful business cases for AMR have common characteristics usually associated with the strategy and process of developing justification and support. Given the challenges, the project’s champions need to (1) adopt a systematic approach to looking at benefits and costs, and (2) build a “campaign” within the organization. While this process is not mechanical, it should be systematic.

A logical starting place for most utilities is to identify the range of available AMR system characteristics and features, and then categorize the benefits created by those features for the utility. Different AMR systems have a wide range of capabilities, from simple gathering of meter readings on a monthly basis (mobile radio), to short-interval monitoring of power quality and outages.

While some benefits of AMR are straightforward, the realization of others will require the involvement of several systems and departments. The following categorization of benefits is useful in developing the campaign to quantify them and win their acceptance.

Simple versus complex. Simple benefits involve only one area, function or department. An obvious example is reducing the number of meter readers needed for on-cycle reading. Complex benefits depend on multiple systems or departments. The identification of abnormally high or low consumption, for example, depends on integrating the meter reading data with consumption histories in the customer information system.

Direct versus Indirect. Some benefits are directly related to the capabilities of the system. For example, the ability to create customer load profiles is directly tied to the system’s ability to obtain numerous reads per day from the meter. Indirect or secondary benefits rely on some process or chain of events. The utility’s call center, for example, may experience a reduction in call volume as a result of eliminating estimated reads. Distribution system operations staff might use missing reads from the AMR system to identify areas of power outage, or detailed circuit related consumption data to balance loads on capacitors and transformers.

Operational versus strategic. Operational benefits pertain more to reductions in operating and maintenance costs or improvements in system reliability. Strategic benefits deal with competitive positioning or long range corporate objectives such as asset optimization or customer retention.

Tangible versus intangible. Tangible benefits can be put in monetary terms; for example, a reduction in staff salaries and overhead. Intangible benefits can’t easily be put in monetary terms, although sometimes they can be quantified. Intangible benefits might include improved air quality and traffic congestion from having fewer vehicles on the roads, improved customer satisfaction, or enhanced corporate image. The utility must not undermine its business case by eliminating obvious benefits because they are difficult to quantify.

Any such categorization will create some gray areas, and it’s important to put these in context. Figure 2 maps key functions and strategies in a utility. Often, the more direct benefits are larger, but this is not always the case. For some utilities, the indirect or strategic benefits have clinched the business case. What’s important is that the farther away the team reaches from the lower right hand corner to find benefits, the more complex, indirect, strategic and intangible they will be, the more people are involved in quantifying them, and the more people there are to convince.

Steps in the Business Case Campaign

With few exceptions, utilities that have created successful AMR business cases have gone through a process of building support and consensus. The following methodology, extrapolated from the experiences of several projects managers, will help ensure the maximum in expected benefits and a firm handle on the appropriate technologies.

The systematic approach involves the follow steps:

- Get educated. The team must educate itself concerning the utility’s internal drivers and opportunities for savings, as well as its corporate strategy, by identifying and gathering perspectives from all stakeholders in the project. This is often accomplished by interviewing key people. Interviews also help position the project and give team members a sense of the challenges ahead. The team should become familiar with available technologies, what other utilities are doing, and the regulatory and competitive environment in which their organization operates.

- Craft a vision of the ideal AMR system that addresses the key drivers and supports the corporate strategies. For example, in addition to eliminating estimated reads, it might provide detailed consumption information to help shape customer loads, or monitor outages to help shorten response times. Each of these objectives may depend on several facets of the technology. The vision will be multi-dimensional and complex, involving other systems and functions across the organization.

- Frame the business case for the stakeholders. In a meeting or workshop setting, establish the project premises and a timetable, and get stakeholders’ commitment to help the investigation. Develop a collective vision, identifying the potential benefit and cost areas. Review all concerns that have been raised about the project.

- In each of the benefit areas, establish quantitative base information. For example, what is the cost of meter reading for different customer segments? What are the customer service productivity measures? What are the current outage response time statistics? What is the estimate for theft of service?

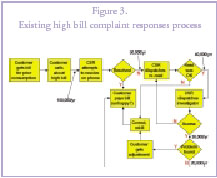

- At a high level, model the key existing processes in the benefit areas and quantify their throughput rates. A simple process model is shown in Figure 3. People who manage the existing processes should be involved in the modeling exercise.

- At a high level, redesign the processes incorporating the vision elements established in Step 4. For example, if all bills are based on actual reads, how does this affect the volume of high bill complaints and field investigations? How does the ability to obtain final reads almost instantly affect the speed, customer convenience and level of effort to process account closings? The redesigned process is shown in Figure 4. In this example, customer calls regarding high bills are expected to be reduced by 60%. This can be translated into a reduction in workload. (Note: this redesign exercise is at the “business case” level; actual, detailed redesign would not occur until system installation was well underway.)

Redesigning customer service processes that involve meter reading is relatively easy. Redesigning operation and maintenance processes in which benefits are more complex and indirect is more difficult. Process redesign is rarely a comfortable exercise; outside facilitation helps. Attempt to quantify the benefits and savings. For some benefits, a range of probability-weighted values will help refine the analysis. - Develop strategic implications of AMRgenerated benefits. For example, how would short-interval consumption data from an AMR system be to encourage customer retention?

- Repeat Steps 6 and 7 for various combinations of technological capability and customer segments (Figure 5). For example, the process to create a final bill will be different for a fixed radio AMR system that produces multiple reads per day than for a mobile radio system. Benefits for residential customers will be different than C&I customers.

- For each key combination, estimate direct AMR system capital, operating and maintenance costs. For complex benefits that rely on other systems (IT integration, new O&M procedures, etc.), estimate the indirect costs (or a range of costs weighted by probability). Assess whether the benefits are wellestablished or largely conceptual. Assemble the benefits and cost elements into an economic and financial model.

- Identify and prioritize barriers, constraints, internal objections and risk factors. Develop strategies mitigating the risk factors.

As this process unfolds, more savings will be “contributed to the pot.” Figure 6 is a composite of the contribution in several different areas for some representative electric utilities. The composite total is about $30/customer/year.

Conclusion

Building the business case is similar to waging a political campaign. It requires leadership, creativity, salesmanship, patience and compromise to overcome the challenges and resistance. A systematic approach to classifying benefits, and a process of stakeholder involvement to secure the savings commitments associated with them, will increase chances for success.

Editor’s Note:

Don Schlenger is a Managing Partner with Cognyst Consulting, LLC, and can be reached at dschlenger@cognyst.com. Ed Finamore, an Associate Consultant with Cognyst Consulting, also contributed to this article; he can be reached at EdFinamore@aol.com.